Throughout their diverse and storied careers, UBC Department of Medicine faculty members acquire a wealth of clinical, educational, and leadership knowledge and skills. We value the experience of our retiring faculty and seek to capture some of their valuable insight and wisdom to share with the UBC Department of Medicine community. We hope that our current faculty will find these perspectives useful as they consider their own career paths.

Name:

Dr. Iain Mackie (He/Him/His)

Title:

Clinical Professor Emeritus

Department/Division:

Department of Medicine/Division of General Internal Medicine

Location:

Vancouver, BC

Dr. Iain Mackie was born in Northern Ireland and raised in Mississauga, Ontario, and is a Clinical Professor in the Division of General Internal Medicine at Vancouver General Hospital and UBC.

Dr. Mackie is an innovative and award-winning teacher at UBC and the University of Western Ontario. He was Citizen of the Year in London, Ontario, in 1993. He won the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal in 1992 in recognition of his national and community service on behalf of persons living with HIV/AIDS. He was also awarded the 125th Anniversary of the Confederation of Canada Medal in 1992 for his significant contribution to his fellow citizens, to his community, and to Canada.

After a 38-year career, Dr. Mackie will retire on June 26, 2022, from the Department of Medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine. He intends to travel, learn to make gin, and pursue his love of hiking and kayaking while continuing to teach medical school students and residents in his retirement.

Are you originally from Vancouver or did you come to UBC from afar?

I’m not a native Vancouverite. My father was a businessman and professional golfer at the Royal Portrush Golf Course in Northern Ireland. He was in Ireland on business, and I happened to be born there. We moved back to Canada in 1964, and I grew up just outside of Toronto in a little city called Lorne Park, which is now Mississauga. That’s where I went to public school and high school.

What was it that drew you to Vancouver?

I went to medical school in Toronto. Then, I moved to London, Ontario, to work at the University of Western Ontario for my residency and fellowship. My career was there for 13 years in clinical practice at Western.

My parents moved to Vancouver Island. My dad was quite ill with chronic illnesses, and my mother was isolated from her family in eastern Canada. So we were looking to come west. I had looked at a couple of jobs at Lions Gate Hospital in critical care, but it wasn’t a teaching position. And my career was focused on the teaching system in a teaching hospital. Barry Kassen, who was/is one of my best friends, thought that maybe there was a position for me at Vancouver General Hospital. That started the process. I was trying to be closer to my family yet maintain an academic career. I had done everything I wanted to do at Western, and I didn’t see any new opportunities there, given the size of the University. So when Barry said there was a potential job in internal medicine at UBC, I leapt at it.

I met with John Mancini, who was the head of medicine at the time, and he was so welcoming and so optimistic about my career path. After a number of interviews, it was simply a done deal. Ultimately, I was recruited to UBC courtesy of John and Barry. They were hugely influential in my willingness to move far away from home.

Jake Onrot is another of my closest friends and ski buddy here in Vancouver. I used to ski race when I was younger, so skiing was an addiction. Whistler Blackcomb being so close was a draw. My knees are suffering now, though.

When you first came to UBC/VGH what was your first official job?

I have always been a clinical faculty member. At Western, there was no distinction between academic and clinical faculty. Dr. Mancini tried to get me into an academic position, but I wasn’t a researcher. Research was never part of my training as a resident or fellow, and I wasn’t hugely interested in research. However, I did do a lot of clinical trials research in HIV/AIDS medicine at Western. The position I was recruited into was as the head of the division of General Internal Medicine at VGH.

Knowing Barry (Kassen) and Jake (Onrot) was very helpful. It’s a difficult system to break into if you’re from outside. My friendships provided a linkage and a knowledge base of the system from the perspective of the people who actually work there. Over the years, many people have tried to move into leadership positions from outside and have not done well. It is helpful if you know people who are here – and I was fortunate to know many people through the Royal College. It would’ve been more challenging to establish a successful career here had I not had those existing relationships.

Did you have any life-changing experiences that put you on a career path?

My original intent in high school was always to pursue medicine. As an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, I did an honors degree in clinical pharmacology. Thanks to the U of T’s advanced standing medical program, I had a really interesting medical school career. You could do four years of medical school in three years. There were 12 of us in this program. We had all done clinical biochemistry, organic chemistry, and pharmacology undergraduate courses, so our first and second years were blended. The first half of my first year was with 12 other people with individual tutors who were also teaching the full 450-person medical school classes. That was a huge eye-opener to me at how attention to individual needs was so important.

After completing my three years of medical school, I was thinking about focusing in Emergency Medicine for a fellowship. At the time, Western had a combined Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine program that was the only one of its kind in the country (it doesn’t exist anymore). In my first year of residency, I realized I wasn’t aiming for Emergency Medicine, but Internal Medicine was my focus. One of the things residents do is teach, and one of the things I found that I was actually really good at was teaching. There are two types of teachers: those born as teachers who come by it instinctively and naturally. And then there are teachers who learn to be good teachers over time. I think I was the former. It came very naturally to me. I seem to have a pretty good understanding of the needs of learners. This realization played a massive role in my career choice, wanting to be in an academic center. Western gave me that opportunity.

I also had an interesting residency. I became chief resident in my R3 year. As part of the full-year chief residency, you could do subspecialty training that year, and I chose Critical Care. I did a year of Cardiology in my fourth year, thinking I wanted to be a Cardiologist. I quickly realized that path was not for me, so I went back into Critical Care.

My first job was as the Medical Director of an ICU at a teaching hospital in London. So my first day of practice, I went to a meeting where we decided on the financial plan for the year with a $27 million budget. I threw up my hands and said: “Nobody’s taught me about this,” so that was the start of my administrative career. It became pretty clear that the powers that be at Western thought I was a pretty good leader and a pretty good teacher. That’s what started my career by circumstance.

One of the life lessons I’ve learned over time is that Medicine (capital M) does terribly at training people for leadership. You take on a job, and then you have to learn on the job. And when you leave that job, somebody else has to take it over and start all over again, which is a terrible way to teach people how to be leaders. That would never happen in business or law. When I began my career in Medicine, you were just thrown in, and you would either sink or swim. Fortunately, I swam and became the head of the division of General Internal Medicine and had an extraordinary ICU career at Western. Both the faculty and the department saw my leadership skills, which led to additional jobs over time.

Dr. Iain Mackie, University of Western Ontario

Career-wise, what are you most proud of?

I’ve had a very privileged career. Neither of my parents worked in medicine. My dad was a golf professional in Ireland, and my mother was a school secretary for the Board of Education in Mississauga. They were both hugely supportive of me going to medical school, both financially and emotionally, so they were my huge inspiration when I was growing up. I am very proud that I’ve exceeded my expectations and my parents’ expectations for me from very humble beginnings.

Dr. Iain Mackie, St. Joseph’s Health Care Centre (London, Ontario)

I’ve had two careers. My career at Western University revolved around HIV care. My biggest accomplishment at Western was creating an HIV care program that I think was the best in the country. I was a leader in that program along with several other people – both in the community as well as academically. We struggled against considerable odds at St. Joseph’s Health Care Center in London, Ontario. The other two hospitals in London refused to look after AIDS patients. I went to the CEO of the Hospital at the time (Sister Mary Doyle) and said, “We need to do this.” Thankfully, she agreed. We had huge support from the hospital but not necessarily from some of my colleagues. We struggled to establish an HIV care program at a time when there was so much stigmatization around HIV and AIDS care. I am incredibly proud that we were able to establish a world-class program in HIV care in a small community in western Ontario. A parallel happened at St. Paul’s here, even though we took a different pathway. We tried to integrate hospital care into the broader hospital at Western instead of creating an AIDS ward, which is what they did at St. Paul’s.

My career took me into the community in terms of AIDS advocacy. We created an AIDS community care program with the AIDS Committee of London, where I was chair of the board. I was also chair of the board that created an AIDS hospice in London. As a result of this work, I was named London “Citizen of the Year” in 1993. The Queen gave me a couple of medals for my service to Canada, so that’s another point of pride. I was in the news a lot at Western; I did about a thousand talks and interviews and talked to everybody interested in HIV care. I spent six months with TVOntario with the educational branch. I was charged with teaching teachers how to teach about HIV/AIDS in the high school curriculum. One of my only regrets when I moved to Vancouver, was that I had to leave this program that I had helped build behind. It was somewhat traumatic to leave it behind socially and intellectually, but you can’t look back. I had a remarkable career at Western, and I’m immensely proud of what a small number of us in the community and the academic world were able to accomplish.

The thing I’m most proud of in my UBC/VGH career was taking the division of General Internal Medicine at VGH and turning it into what I think is one of the best divisions of GIM in Canada — and along with Barry (Kassen), creating a Canada-class division of General internal medicine within the Department of Medicine. That was a huge accomplishment, but it came with struggles. VGH was not particularly academic when I arrived. There was a lot of resistance to forward-thinking within our division early on, especially with some of the older, more established internists. They didn’t want to do new things. Creating a high-level clinical teaching unit structure at VGH that didn’t exist before was a huge accomplishment. It certainly was not done by me alone. We had the support of both the head of the department, Dr. Mancini, and the UBC division head of GIM, Dr. Kassen.

Another proud clinical moment was developing our internal medicine perioperative care program, which has become one of the best in the country. We are attracting residents from all over the country. One of my hopes for my retirement is to develop a fellowship or a clinical year in internal medicine in perioperative care independent of the fellowship program here and make it open to all the fellows across the country to come and learn how to do clinical perioperative medicine.

The final thing is that I’m still considered one of the top teachers in the program – teaching has been my career. I innately understand the learning needs of residents and medical students. Teaching is not an individual event; it’s a group effort. I’ve been recognized for my teaching many times over, and I appreciate it. Still, at this stage, I don’t feel as though I need the recognition anymore. I set out to be a good teacher, and I’ve accomplished that. When I think of the hundreds or thousands of residents I’ve come in contact with over the 38 years of my practice, I only hope some pearls of wisdom have sunk into their brains. One of the most rewarding things is watching your medical students or residents become your colleagues and seeing them establish their own very successful careers academically here at VGH, SPH, and the university. It’s the closure of the loop that makes it so worthwhile.

Dr. Mackie: VGH Rounds

Who was your most influential mentor?

When I was chief resident, the head of medicine at Western was a nephrologist named Peter Cordy. Peter was a tough Englishman who taught me a lot about being a leader just by watching what he did. While he was undoubtedly a tough cookie, he was also fair, and he listened. Dr. Cordy taught me to have a vision about what I was doing and where I wanted to go. He taught me how to listen to people and not be afraid to make decisions. He didn’t always agree with things that I recommended. Still, at least I felt that he’d listened to my opinion and weighed it carefully, and then made the best decision. In addition to being a fabulous leader, he was also an outstanding clinician, and I tried to emulate how he looked after his patients.

In Vancouver, I’d have to say it is John Mancini. He demonstrated those same characteristics as Peter Cordy. He was fair, and he listened and made those hard decisions. I don’t know that I would have moved out to Vancouver if John hadn’t been the head of medicine. He’s been hugely influential in my career here.

I need to clarify that you asked me who my most influential mentor was, but Peter and John are not the only ones. Anita Palepu and I have grown up in the system together since I moved here in 1996. She is a wonderful colleague and leader. When I think about the qualities that I like in leaders – Anita models all of them. Anita is fair, honest, inclusive, and not afraid to make hard decisions considering all of the perspectives that need to be included.

I also feel influenced by the people who make up the system we work in. I talk to everyone, the porters, nurses, unit clerks, and custodial staff; I speak to them all. I try to teach my residents- if you want something done, you’ve got to know people. Understanding a broader perspective is another good sign of leadership.

What advice would you have for a junior faculty member in your field?

Get to know people. Getting to know people and having them get to know you is critical in medicine. Whether you’re in an academic center where patients flow through the emergency department, you don’t necessarily have to cultivate relationships to get patients. In the outpatient world, you do need to nurture those relationships. People know you and your skillset and will reward you by referring patients. I think I’ve successfully built those relationships with other people in the system – at VGH and SPH and in the university system.

It comes down to the three A’s: being affable, able, and available. Get to know people, and they will respect you, and they will do anything for you.

What advice might you have for a senior faculty member approaching retirement?

Plan your retirement. The worst thing I can think of is to stop working and not have anything to fall back on.

My exit strategy was partly driven by COVID-19. I gave things up over time. I stopped doing CTU in December, not because I didn’t like it anymore, but because the call was becoming really onerous. I gave up my outpatient practice in January. Now I’m just doing a little bit of work in the hospital with our perioperative team and resident clinic. I’ve staged my retirement over time, giving me time to think about other things to do.

Another bit of advice I have is to continue to be good at what you do. It’s easy to stop teaching; it’s easy to stop caring – that’s a huge mistake. You’ve reached this point in your career because you are good at what you were doing, don’t let that slide. Maintain high-performance standards and skill sets until you stop working. If you stop caring, then you might as well go.

What kind of activities did you have in mind leading up to your retirement that you were interested in exploring?

There are two aspects: what you will do medically to “pay back” and what you will do personally.

I have had a very privileged career. Some years ago, I got involved with Dr. Amanda Hill to start the global health program. I’ve never gone to use any of my skills in developing countries. Depending on my health and the state of the world, one of the things I’m keen on doing would be to go overseas- not to practice medicine but to develop teaching skills in the medical programs in those countries. I pride myself on teaching how to do physical examinations- it’s been a huge component of my teaching career. So if I go to Africa or South Asia and teach the teachers how to be better teachers, that would be a better long-term payback than just going for a month to work in a medical clinic.

Academically, I’d like to create a formal fellowship program in perioperative medicine within the university system. I’ve also been asked to help deal with professionalism issues after I retire and will be going back to teach medical students.

Personally, I’ve been interested in learning Spanish. We have very good friends in Madrid, and I go to Spain a lot, but I am terrible at Spanish. One of my first goals is to spend a couple of months in Spain and hire a tutor to help teach me conversational Spanish. The conversations I currently have with my friends always revert to English after a few sentences.

I also really like gin – it’s the only liquor I drink. There is a course offered on the North Shore that teaches you how to make gin. So I’m going to take that course.

I’m also very outdoors-oriented, so I’ll also do some hiking (where my knees permit). We have a place over on Bowen Island where I like to do some kayaking. And of course, I’ll do a lot of crossword puzzles and watch a little bit of Netflix.

What was your last day of CTU (Clinical Teaching Unit) like?

Dr. Iain Mackie with residents on his last day of Clinical Teaching Unit (CTU)

Most of my career has been around the clinical teaching unit. My last night of call was also my last night of CTU and the residents brought me a little cake, and we took some photographs. It was actually wonderful. Giving up those things was way less traumatic than I thought. Don’t get me wrong; I do miss it. But part of me says I’ve done enough, and it’s time for other people to pick up the torch. I miss the medical students and residents. I don’t miss the stress or the call.

It’s an incredible amount of stress. I think patients are sicker in the medical wards now than in the ICU at the beginning of my career. Then you throw a pandemic into the mix, and it becomes hugely stressful. Residents deserve an enormous amount of credit for their skillset and ability to do ICU under these circumstances at the beginning of their careers. They’ve stepped up to the plate, and oh boy, they’ve learned very quickly.

Do you think beginning a career in the middle of a pandemic will serve residents better in the long run?

That’s a very interesting question. I think physicians need to be adaptable to new environments. I started my practice at a time when some of the first patients I saw were AIDS patients in ICU who were all on ventilators and ultimately died. We had to adapt to this new reality of this epidemic of HIV, which has hugely different psychosocial circumstances than COVID-19. But the parallels are there. At the resident retreat this summer, I’m going to give a talk about the parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the 90s HIV/AIDS epidemic. The sheer volume of patients coming through in a short period of time is hugely stressful. The residents, to me, have proven their mettle by being adaptable to circumstances. This adaptability will serve them well in the future, even though you can’t see it when you’re in the middle of it. All you see is the trauma, the suffering, and the anxiety that we have as caregivers.

It’s hard to see that it will make you a better doctor when you’re on your third night of call in the emergency room on CTU admitting twenty patients. You don’t see it in the middle of that. Ten years later, you’ll look back and say, “It was stressful, but I learned a lot.”

Medicine (capital M) is a very conservative profession; it doesn’t necessarily like change. It can be quite inflexible and learning to be flexible benefits everyone in the long run. To create systems that help patients, we need to be adaptable. That’s what I heard when I arrived in Vancouver: “We’ve never done it that way before.” And the suggestion of trying it another way was met with resistance. If I heard it once in my first year in Vancouver, I heard it twenty times.

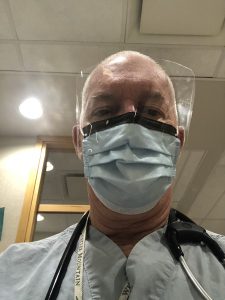

Dr. Mackie in COVID-19 times

Do you think the next generation of physicians will be progressively more inclusive and flexible than their predecessors?

Look at what’s happening politically in the United States. In the 60s and 70s, these people were the hippies and the drug culture, and now they’re some of the most conservative people on the planet in some respects.

Age does lessen your flexibility- you don’t want to change. You have a vested interest in things staying the same, especially if it benefits you.

It is a new era. We now have a broad mix of people of all races, cultures, and genders. This diversity will absolutely change medicine. The fact that more than half of our residents are women will radically alter the way we practice medicine for the better. It’s gone from a male-dominated and conservative career to something multicultural and totally inclusive. With excellent role models like Anita (Palepu) in leadership positions who lead by example and make sure that diversity and inclusivity are incorporated into everything we do, I have great hope for the future. I think our residents are the best in Canada. Our residency program is one of the best in the country, without question. There’s not one resident that I’ve come across that I would not want to look after me or my mother.

What will you miss most about working at UBC?

The people. Those relationships I’ve built over the years are so important to me. My partner has really helped me with that. If there’s one person I’m so grateful for in my life, it would be my partner Bill Graham. I can be quite introverted, but Bill has taught me how to open up and be comfortable in my own skin over the years. Being a gay physician in the system was really hard. He has been my rock and has supported me throughout my entire career. We calculated it the other day – I’ve been on call for ten years of my thirty-eight years in practice. You have to have a strong relationship to endure a career with these demands. I’m grateful that he has helped me find a work-life balance.

Any final thoughts?

I have had the most privileged career because I’ve never regretted my choices. Generalism appealed to me, and I’ve never looked back and wished I’d done something more specialized.

Moving to Vancouver was the best decision I made. I think what I’ve contributed to the university and the faculty and department of medicine, I hope, has set an example. I hope I’ve left something of myself within the system, whether it’s a resident who learned how to be a teacher or a medical student who learned how to be a good doctor. I hope to leave my career on my terms with my head held high, saying, “I’ve done the best job possible and have no regrets.” I hope I’ve not hurt anyone, and I hope I’ve done the best job I could and that people appreciate that. Hey, the Queen appreciated it! I have the medals in a drawer to prove it.

The Department of Medicine is incredibly grateful to Dr. Mackie for agreeing to be interviewed and being so generous with his time and insight.