Throughout their diverse and storied careers, UBC Department of Medicine faculty members acquire a wealth of clinical, educational, and leadership knowledge and skills. We value the experience of our retiring faculty and seek to capture some of their valuable insight and wisdom to share with the UBC Department of Medicine community. We hope that our current faculty will find these perspectives useful as they consider their own career paths.

Name:

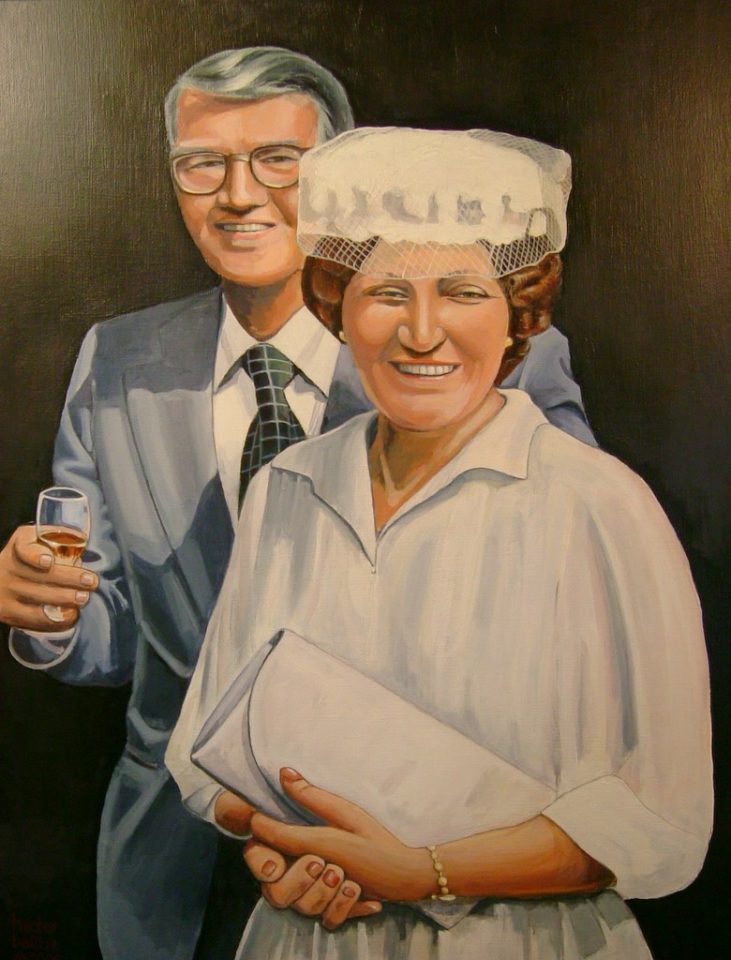

Dr. Hector Baillie (He/Him/His)

Title:

Clinical Professor

Department/Division:

Department of Medicine/Division of Community Internal Medicine

Location:

Nanaimo, BC

Dr. Baillie is a Clinical Professor in the Division of Community Internal Medicine.

Dr. Baillie hails from Scotland, where he completed an undergraduate degree in mathematics and a Masters in biomedical engineering before completing his medical training at the University of Glasgow.

Dr. Baillie has worked in British Columbia since qualifying, first in Mission (1987-2002), then Nanaimo (2002-2023). He retired on April 14, 2023. He hopes to fill his time writing, painting, travelling, and kayaking on the Bay. And of course, he will take his beloved chocolate lab Cassie for walks on the beach.

Where did you grow up?

My twin and I were born in the distillery manager’s house in Bowmore, Isle of Islay, Scotland. My father was the manager of the Bowmore Distillery. You could say that I was baptized with scotch. We moved to Glasgow, and I went to a reputable grammar school. I enjoyed it. I signed up for a degree in Mathematics at the University of Glasgow, followed by a Masters in Biomedical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde. I turned down a few jobs offers, and then followed my twin brother – doing Medicine at the UofG.

After my intern year, I emigrated to Canada. My dad’s company (Chivas) is owned by Seagrams Canada, and he would meet periodically with Sam Bronfman in Montreal. I thought, “This Canada place looks interesting,” so I emigrated to Winnipeg. A bit of an eye-opener. Friendly place, but hot summers and long cold winters. After 4 years of training in Medicine, and one in Anaesthesia, I thought I was qualified to look after people. Especially in Intensive Care.

Did you have any life-changing experiences that made you want to pursue Medicine?

Three things happened to get me into Medicine.

The first thing is that my father died of a heart attack when I was finishing Mathematics. He had a subendocardial anterior myocardial infarction, but in those days, there wasn’t access to the same medical wizardry that we have today.

The second thing was a biology course I took in second-year Science – that blew me away. I thought, “This is where I want to be.”

And third, my brother was doing very well as a young doctor, so I thought, “Why don’t I just do medicine?” My mum said, “Don’t! That’s another ten years of training!” Note to self: always listen to your mum.

If you had to do it again, would you still choose Medicine?

Getting from Mathematics to Medicine isn’t a straight progression at all. Mathematics is a vertical science where you deduce things from top to bottom, whereas Medicine is an associative science where you see both sides. I guess they’re opposites.

I turned down a Computer Programming job with IBM, Systems Analysis work with Barr and Stroud, a government job at Porton Down, and Operational Research with British Rail. I owe a debt to the British education system, which supported me with a grant for all of my training. Then I emigrated to Canada, which I felt a bit guilty about.

If I had signed on with IBM, I suppose I’d be long retired with Microsoft shares and some villa in the south of France. Maybe I’d be the CEO of something. You can spend your whole life in Medicine, and you’re never going to be a CEO. I chose to be a captain in the trenches rather than a general in HQ. I think I did a good job, but it was an uphill battle keeping ‘academic’ in the community.

What brought you to British Columbia?

I was the anaesthetist during a coronary bypass surgery at Winnipeg General. One of the infusion pumps started to alarm. “Ring-ring, Ring-ring.” I couldn’t figure out which one it was. One of the nurses approached me with a cell phone and said, “It’s for you” – in the middle of the operating room! Confused, I took the phone and said, “Hello?” It was Dr. Terriff, from Mission, BC, recruiting me to their hospital.

He suggested I visit British Columbia. I looked out the OR window. It was cool, and snow was on the ground. That long-May-weekend saw me fly to BC and check things out. Daffodils done, tulips out, sun pouring down on towering mountains. I liked the place, bought a house, and flew home.

I cut my anaesthesia training short and started as a solo internist; that was a brave thing to do in 1987. The most significant decision was to forego an academic career at Winnipeg General Hospital for a solitary job in a small town (population 25,000 then, 45,000 now). Perhaps I should have thought things through or done a locum. I had no house staff, limited resources, and few associates to consult with. I was on call daily for most of those 15 years (I loved it). I had to develop skills in self-reliance, leadership, and continuous learning. My wife, Sheena, was a first-class nurse and loved this small hospital.

Many students think that because they are trained in the Ivory Tower, they must stay in it. That’s sad because we all have the same type of patients, and the opportunity for development is enormous when you’re on your own. You’ve got to figure things out independently, and it can be quite a buzz. Rural medicine should never be an afterthought. Abraham Flexner once said, “Rural is where you send the best” – because the nature of the work demands no less. I’ve seen a lot of people come up behind me who have grown into incredibly strong doctors.

Who were you influenced by and/or who was your most important mentor?

Independent, strong thinkers. As a medical student, I learned from an internist called John Dagg. It was early in our clinical training. Six of us sat at a patient’s bedside and asked questions without any real experience. Before long – without tests or x-rays – we figured out he’d had a right Pancoast tumour, Horner syndrome, and an ipsilateral cerebellar metastasis. I thought, “This is the stuff of Arthur Conan Doyle; what fun.” We went next door to the Hematology Unit, where a young Indian man was nursing a swollen knee. We asked him the usual questions, “Did you injure it? Do you have arthritis?” And then I realized, “What are you doing on a Hematology ward with a sore knee? Do you have a blood disorder? Do you have hemophilia?”

I thought this was great; this is what I want to do. I want to be Sherlock Holmes, MD. That was many years ago. Recently I thought, “Whatever happened to John Dagg?” I looked him up – he’s still alive! He was my career exemplar. Imagine having somebody who can act like a magnet to change your whole mindset and point your career in a new direction. I hope everyone finds that individual (and that you get to thank them 50 years later). Of course, I’ve been privileged to work with and learn from great people – like Peter Warren, Morley Lertzman, Robin Kuritzky, Laird Birmingham, Vic Huckell, Anthony Dellasiega, Vicki Bernstein, Mike Kenyon, David Forrest, and …. too many to mention.

As for formal mentors, I don’t think I had one. Everyone should have one or two. I’ve mentored several people in my time who became successful and respected physicians, but it wasn’t easy. We should be trained to be mentors. I wish I had one in my career, but no, I just made all the usual mistakes. Next time, I’ll put my hand up and say, “Can I have a mentor, please?”

Tell me about your experience as a physician in the Division of Community Internal Medicine

In my day, when you left tertiary care training in a big city, an iron curtain would come down, and you were on your own. When you left the hub, you never got contacted again. I wanted to teach and show people how to do procedures, so I engaged with Family Practice training programs in both Mission and Nanaimo. Over the years, I’ve given about 430 lectures. Many students came my way, and I got them enthusiastic about rural practice. I did some research and some RCPSC examining. I didn’t get the feeling I belonged to a Division or was supported by one. Over time, residents and fellows came to us and were surprised with what we could impart and said, “Wow! This is really fun!”

UBC couldn’t tell me who was in the division, about curriculum development, or what the teaching and research goals were. I sense things are changing for the better. Dr. Jaworsky is now the new Head of the Division – able to encourage eager and bright minds to work anywhere. The new SFU Medical School will work on a distributive model – you send people out to learn, you don’t bring them in. You have faculty in rural areas who are highly skilled in teaching and research and can develop local curricula. That hasn’t been the model of UBC until now. I worked my way up the ranks to become a clinical professor seven years ago, but how often was I asked to lecture students? Never. Pity.

Faculty should come and lecture here, and we should go and lecture there. Rural medicine sites are a goldmine for teaching – it’s where the patients are! Patients are moving from big cities into more affordable rural communities. They get the same diseases and want the same level of expertise afforded to them wherever they live. I’ve been lecturing on the value of community internal medicine for decades.

What is the highlight of your career?

There are highs and lows. The low is pretty obvious. I put 15 years of very hard work into building up a hospital in Mission. I had built the ICU there and established the stress lab and pacemaker clinic. In April 2002, the Fraser Health Authority, ‘in an act of infamy,’ decided to close it down – in 15 days. That decision changed my career dramatically. I moved west.

Highs? Starting a journal (Canadian Journal of General Internal Medicine) and being its editor for six years. Examining for the Royal College. QI projects for Doctors of BC and College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC. The biggest high happens every day. You get to save lives. In intensive care, we thrombolized patients, floated pacemakers, ventilated the sick ones, and dug them out of shock and arrhythmia. Our team in Mission was saving at least three lives a week.

Even in the office, the gains can be huge. Last year, John S came to me and said, “For some time now, I have had this crushing chest pain when I do the slightest thing.” So I thought for a second and said, “Let me see. It’s Thursday afternoon. Let me type up my consult note, print it off, drive you to the hospital, walk you into the ER and find you a cardiologist and a bed. You’ll be kept in over the weekend; you’ll get your angiogram on Monday and your bypass on Tuesday.”

I phoned him two weeks later and asked how he was doing. He said, “Quite well, but I don’t understand how it happened so fast!” But I do: it was a pay-it-forward day. On Thursday lunchtime, I went to McDonald’s for a cheeseburger and shake. The cashier at the drive-thru said, “The lady before you took care of your bill; it’s a pay-it-forward day.” So, I thought I should go above and beyond this afternoon. And that’s when John came along.

Everybody you heal – it’s not one person you’re healing. It’s their partner, their kids, their colleagues, and all the people in their life. Families are so relieved because it’s not on their shoulders alone. They have someone that they trust and can call when things start going south.

What advice would you have for a junior faculty member starting out in your field?

Only select a final career path after you’ve checked out all your options. So many people think they must decide to be a nephrologist in third-year medical school. You’ve just shut so many doors. How do you know when you have yet to try addiction medicine in Sudbury or internal medicine on Saltspring Island? Don’t make decisions too soon.

I give my patients lots of time in appointments to get everything out. If you’re talking, you’re not listening. And if you’re not listening, you’re not understanding your patient. I’ve been a patient, and you always learn by being a patient. The best question you can ask a doctor is: “If it were you, what would you do?”

And finally, always think about your partner and what they need. I was a mathematician who got appendicitis, and my wife was the nurse who looked after me. The NHS lost a good nurse when she married me. It would be best if you dovetailed both of your careers. Take time for your partner and your kids. While working ultra-hard to do the best for my community, I would come home at 8 pm. What did I miss? The kids’ bedtimes and reading them stories. Now they are thirty-five and don’t need me to put them to bed. The new philosophy that young grads have is a ‘work-life balance.’ They’re probably right.

What advice might you give a senior faculty member approaching retirement?

Retirement is a bit like landing a plane. You have to lose airspeed and then altitude, contact the tower to let them know you’re coming, jettison some fuel, then after you land, you have to switch off the engine.

I went back and did my 41st-year reunion in 2022, and all my colleagues there retired at 55 with big pensions. They all said, “Are you still working? Ha! We’re all out on the golf course every day!”

I love my work. I meet nine strangers every day, and they all leave as friends. Where else can you say that? I’ve either educated them or influenced the course of their illness or their loved ones’ illness. It’s a great job.

When you retire (or shuffle off), you will be remembered by how you influenced other people and not by how much money you made. You won’t be remembered by the depth of your keel but by the wake you leave behind.

How do you plan on spending your retirement?

I sometimes ask my patients how they enjoy their retirement years, and most say, “I don’t know how I could have ever worked; there is so much that I have to do.” My problem is that I haven’t known much outside of medicine. I have a few hobbies, but in common with many physicians, medicine was a driving force. I’d do systems reform work any day – but that’s not likely. I retired on April 14th. I’ve agreed to do some locum work. Waitlists are huge, and the system could use a hand. I never got a thank you from a Health Authority – ever! But the tax man says he’s missing me already.

I’ve written a couple of books (“Casebook of a Community Internist”), the first of which will be out in 2023. I might go back to painting, and kayaking. And travel, health permitting. But let me finish by thanking everyone (including my wife and family) for making this a career to reflect warmly on, with no regrets.

As they say in Scotland, Sláinte!

The Department of Medicine is incredibly grateful to Dr. Baillie for agreeing to be interviewed and being so generous with his time and insight.